Mark The Date

There has been a fair amount of discussion around calendars and time-keeping lately (

[1] [2] [3] [4]). Time is the important but ill-considered corollary of space that girds location-based exploration play. As Eric at

Methods & Madness notes, much has been made of the Quantum Ogre problem, which constitutes railroading-in-space (whether you go east or west, you meet the ogre), but the practice of railroading-in-time, lets for now call it the Quantum Birthday problem, is generally more accepted (whatever day you arrive in town, it is the ogre's birthday).

This is an issue that I flagged in my review of

Willowby Hall, as that adventure assumes a floating timeline of events anchored to the point in time at which the party arrives at the titular manor. In my review I expressed that this felt "videogamey" to me, and though I proposed that within a campaign setting one could simply assign the events of the module to a specific date and time in one's calendar, there was an element of this that felt unsatisfying to me. While old-school play proceeds with the assumption that not all content will be explored, when the content is a more-or-less static locale, there exists at least the possibility that it may eventually be visited, or at the very least recycled into different venues. A time-specific adventure feels, perhaps aptly, far more fleeting; if it is missed, it is missed forever (assuming that it is a unique incident, and not a regularly reoccurring one).

That being said, there are a number of techniques, new and old, such as rumours or job boards, that are used by Referees in order to direct players to the spaces where particular adventures occur, and here I would like to outline such techniques that can be used to orient players along the temporal axis as well.

I draw inspiration here from the Shin Megami Tensei: Persona series (or at least entries 3 to 5) in which the calendar serves an incredibly important role in directing player activities. The calendars in each game forecast different predictable or semi-predictable events (phases of the moon, weather, schedules of targets) that circumscribe the possible actions the player can make on a given day, as well as provide deadlines by which certain activities must be completed.

|

|

Persona 4 may provide the most interesting example in this case, as its calendar system is the most dynamic. In Persona 3, the calendar is marked by phases of the moon, which are regular and predictable, and the player is shown the entire month's calendar in advance. 4, by contrast, relies on a weather schedule which, while predetermined in the game's code, is not so easily inferred through natural logic on a blind playthrough; only a week is shown in advance. Therefore, while in 3 the amount of time given to complete the next phase of the dungeon will always take roughly 27 days, in 4 the deadline is based around when the next foggy day will be; if one spends too much time tarrying with other activities, they may find themselves hard pressed to finish the dungeon in time and avoid a fail state. Notably, despite this irregularity, the rules for what events and activities occur during which weather states is predictable.

I will list several techniques to be used in conjunction with a calendar and a campaign timeline of events to forecast an ordered logic around time that can be used to clue players in on when the action is, so to speak. Like the principle behind the Three Clue Rule, these techniques have their effect amplified the more are used, and the more redundancy there is, particularly when you wish players to have the possibility of discovering extremely unique time-sensitive events (e.g. occurs on one particular day, or even a few particular hours, and then never again).

Day & Night

The first technique, and the one already most common, is creating a differentiated list of encounters and events that happen during the day vs during the night. This is generally for predictable, reoccurring patterns of behaviour rather than unique events, though it can be used to add a dimension to those as well. Players can use ecological knowledge to know that if they wish to collect a bounty for owlbear hides, it is better to attack during the day when they sleep; if they are investigating murders in a village where victims are found desiccated in their beds with two suspicious marks on their jugular, perhaps they had best set a stakeout at night.

Phases of the Moon

This is very similar to the above, on a slightly longer scale, and with a slightly more ethereal nature. Beyond werewolves and lycanthropes, one can reinforce the logic that the veil between the natural and supernatural is thinnest at the time of the full moon, as well as the observable real life phenomena that crime and public disturbance is at its highest levels. I'm sure this has applications for maritime adventures relating to the tides, but I'm no waterologist.

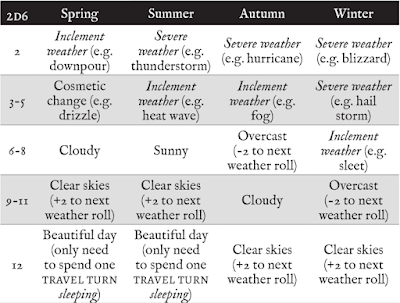

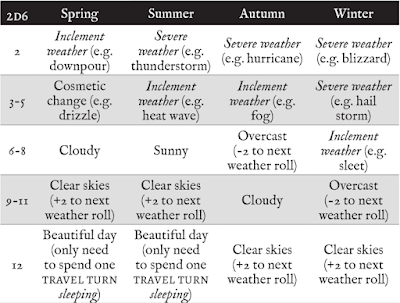

Seasons & Weather

Again, applying quasi-ecological principles here gives players a heuristic for what kinds of adventures, events, and creatures may be encountered when. On the basic level, note which animals and monsters are inactive vs active in different seasons and create random tables accordingly. From there, one can also extrapolate when in the timeline certain adventures may occur; a module that heavily features ents likely won't be happening in the winter.

The use of weather tables tied to different seasons also defines the conditions in which certain events might occur. Notably, in Persona 4, certain rare and beneficial events can only occur during rainy days; applying this logic in a campaign setting may be interesting in order to force the party to venture forth in less-than-ideal weather in hopes of finding say, a mystical treasure-laden island that only appears in the lake during a thunderstorm, or a mysterious wish-granting demigod that moves through blizzards. If you wish to be an extra-diligent dungeon master, you could create different encounter tables that are sensitive to day vs night, the season, and the weather.

|

| The Errant Weather Table |

Depending on how you structure weather in your game, it will also give you an idea of what your players will be doing during the different seasons. Given how inadvisable it is to travel during winter in Errant, I anticipate players spending the season hunkering down in a settlement. So, winter is the season that I will load up with all the urban adventures, murder mysteries, and court intrigue.

Festivals & Habits

We move from the purely ecological to the social dimension of time (though of course the two are mutually reinforcing). These should always be known to the players and clearly forecasted on the player-facing calendar (if the players have a map, they should also have a calendar): when and where are the major festivals and events in the setting. Make sure these are big and impactful, something the players will want to make an effort to go to, rather than just something that just occurs. Like Mardi Gras in New Orleans, not like the feast day for St Francis of Assissi; a destination event with a clearly unique benefit/upshot. Its easy to seed specific adventures around these, as such nexuses of activity will always have something notable happening, but also a sly and enterprising Referee can place specific adventures along the most common routes to the location of the events.

At a lesser scale are the sort of regularly reoccurring social events, like market days, church days, or even NPC schedules and routines.

Both these larger scale "festivals" and smaller scale "habits" should be mirrored in the underworld/wilderness, not just civilization. Is there a week perhaps where all the dragons in the region meet on a mountain summit for a moot, to resolve grudges, redraw borders, renew allegiances, and pay debts? Do the fae commemorate each solstice with a procession of The Wild Hunt? Do the Goblins have Goblin Mardi Gras?

The Market

The seasons dictate production, and production dictates activity. Being able to signal to players the state of the economy can provide yet more clues, and give guidance to the Referee about what types of adventures will occur. Economically depressed cities will have high incidence of crimes and political instability; prosperous regions will have frequent caravans patrolling routes that will make attractive targets for bandits and intelligent monsters; areas rich in natural resources may be targets for invasions, assassinations, or coups.

To some extent this is also an element players can impact. At sufficient levels, your typical adventuring party wields enough purchasing power to grossly destabilize regional markets (this post is a good example). Errant likewise attempts to account for this through an abstracted inflation system determined by how much Supply (an abstract item resource) the players purchase in a settlement over the course of a month.

|

| The Errant Inflation Table |

Similarly to seasonal/weather dependent encounter tables, the Referee then may wish to have different city encounters and adventures ready to deploy based on the economic conditions.

To more explicitly tie this into an adventuring context, one could utilize

quest boards/adventuring guilds that forecast what kinds of jobs are likely to occur when. This could either be explicit, like a sign that declares "GOBLIN SEASON OPENS IN 2 WEEKS", or perhaps just the regular information conveyed by other members: "yeah, winter its all the shit bodyguarding jobs, but if you make it up north before the first thaw you get your first pick at those lucrative caravan jobs."

Information

We could think of this as time-sensitive information vs time-agnostic information. Time agnostic information is the stuff that lets players know about the regular ecological and social rules of how time is structured: when the seasons change, when Goblin Mardi Gras is, where the king settles down for summer court, etc. Some of this will be immediately obvious (day vs night), a lot will be covered by the player-facing calendar (seasons, festivals), and others will have to be discovered either by lived experience (getting attacked by witch owls at night) or information gathering (the local yeoman telling you the migration pattern of the deer, the above example of the adventurer informing you what jobs are typically available when/where). Having a variety of NPCs with specialized information on specific subjects that players can access is important for conveying this kind of knowledge: rangers and druids for ecological knowledge, clerics and wizards for the supernatural, and bards are pretty much one stop shops for everything else.

Time-sensitive information conveys to players when the more specific events are occurring, or will occur. Rumours are generally quite useful for this, although they are not generally the fastest or most specific. But for broader scale events, such as "there's rumour the Mountain Lords are marshalling their warhordes to march come summer", they're perfectly adequate. Sages, oft underutilized, I think come into their own here, especially if you run them as having oracular powers. Provided players pay a fee, you have the opportunity to hand out information on incredibly specific and unique events: "on the 17th day of the 3rd month, there will be an attempt on the monarch's life."

On a broader, more infrastructural level, the party can hire retainers whose sole purpose is to observe and report from different areas of the setting; say, one such person posted in each of the four major cities of the realm. Of course, the players will need to invest in some communication network in order to facilitate speedy arrival of such information, whether that be a courier service, messenger pigeons, or magical message sending. Ideally they would also have invested in reliable and fast transportation in order to capitalize on such information; vehicles and mounts and ships, and at the domain level investment in infrastructure like roads and (if a higher magic campaign) teleportation networks (I would, if running this, circumscribe such networks to only be able to have a limited number of nodes and only be situateed and transport through leylines, in order to implement a strategic layer for the players in the most efficient configuration of this network).

This can also be baked in on the level of systems & procedure if using an

overloaded encounter die. A corollary to the "encounter sign" at the dungeon or wilderness level is a "forecast" of the next major campaign event that will occur, or perhaps the next one in the region. Using this mechanic also allows one to add some dynamism to destabilize otherwise staid or static timelines by randomly introducing new threats, developments, disasters, etc.

Cheating, of a sort

With all of the above providing lots of avenues by which players can orient themselves to when adventure is happening, here are a couple of ideas to still make it easier for them to access that content.

First is taking advantage of character rosters and retainers. Players can distribute them strategically throughout the setting, such that if at the end of one session they hear that the Tomb of Tarluk will open for one week before closing again for a century, they can start next session assuming control of their characters in the region already near the Tomb of Tarluk. Metagamey? Perhaps. But we're playing a game, and the aspect of player skill was finding the information and having the setup to be able to capitalize on it; plus if a PC several miles away is aware of something happening, surely the one located closer to it is too.

Second is affording some in game method of time travel. If you've got adventures in your campaign like Willowby Hall that essentially take place on one day specific day in your calendar, and your players discover it in the aftermath, I would also place around the campaign world a limited number of items, locations, or characters that allow the PCs a circumscribed form of time travel. Essentially I'd let them go to a specific place and time for X hours before being brought back to the present. Make whatever magic sends them off specifically have some sort of causality limiter so you don't have to worry about all the butterfly effect ramifications and paradoxes (unless that's your bag); they keep the treasure and etc., dead NPCs remain dead, everything else in the timeline remains mostly intact.

In Practice

Lets use the above to try to fix my problem with Willowby Hall, both situating it within a calendar and hopefully giving the players enough information to be able to navigate to the adventure on time.

First, Bonebreaker Tom lives in a flying castle near the town of Turnip Hill. So regardless of time, that floating castle is there, the town is there, and Willowby Hall itself is nearby, discoverable at any time. The floating castle is probably a known landmark which the PCs can easily learn about. Alternately, instead of it being static, the castle could move around the map, and with a bit of information gathering its route may be inferred. Either way, lets say that, at the time the adventure takes place, the castle will routinely be near Turnip Hill.

So when should the adventure take place? Well, the instigating event revolves around Mildred, the golden egg laying goose. Geese lay eggs typically, between February and May, in the spring. We can pick any date there and stick to it.

Lets assume that Tom, while reclusive, occasionally has dealings with humans. Its known by now that in the spring time, around Turnip Hill, there arrives in the local market an influx of golden eggs. This means that there's a bit of a boomtown vibe, and so adventurers in particular journey to the region to take advantage of the economic activity in the area. Hell, lets even put a fairly large festival that occurs in Turnip Hill a day or two before the adventure begins, given all the merchant caravans that will be arriving in anticipation of the purchasing power that will arrive in the region soon. This of course also provides backstory behind how the NPC adventuring party would know about Tom's goose, and where his castle would be.

Enterprising players who want to get some more information on what they might find nearby Turnip Hill might pay a sage, who will directly tell them when and where the events of Willowby Hall will occur. Less solvent players may have to settle for the rumours from a bard, or from a local tavern, where whispers of a planned heist into Bonebreaker Tom's castle may be circulating. Players who miss going to this region during this period will soon hear about the aftermath of Bonebreaker Tom's rampage via rumour, and may decide to either follow the trail of the giants and the adventurers, or go on a quest for a time travel Macguffin to get back to the start date of the adventure.